Group Members (Alphabetical Order)

- Malvika Badrinarayan

- Hong Yuan Chang

- Mugdha Jadhao

- Ishan Nadkarni

- Prasoon Sinha

- Nithyashree Srinivasan

Introduction

Twitter is an extremely popular social media platform, containing millions of daily active users (although given the recent controversy surrounding the recent change in management and mass amount of layoffs by CEO Elon Musk, this remains to be seen). As a free and easy-to-use platform, users engage in international news, politics, sports, memes, and a variety of other topics. However, many users do not realize they often engage with Twitter Bots, which often tweet malicious links, interfere in elections [1, 2], spread fake news and propaganda [3], and attempt to steal user data. Bots are simply automated programs that attempt to co-exist with human users by imitating genuine users. Given the unquestionable importance of user safety and maintaining the integrity and respect of social media platforms, many researchers have focused their attention in creating scalable solutions for identifying Twitter Bots. In this blog post, we do the same by exploring and improving on the recent research advances in Twitter Bot detection.

TwiBot-20 Data Set

We use a subset of the TwiBot-20 Data Set [4], a comprehensive Twitter Bot detection benchmark. Presented in the International Conference of Information, Knowledge, and Management 2020, this is the first publicly available data set of Twitter users that includes follower relationships. The authors of this data set leveraged the Twitter API to collect three modals of user information: semantic, property, and neighborhood information. To create a diverse user data set (unlike many of its predecessors), a breath-first search algorithm was used to select users from the Twittersphere (graph of Twitter users, where nodes are users and edges represents a connection between two users). Below are some of the unique features this dataset contains relative to the three modals collected:

- Semantic: user tweets, retweets, and replies

- Property: follower count, following count (friend count), verification status

- Neighborhood: users followed and following (in the form of Twitter ID numbers)

Data Exploration

In order to obtain domain knowledge in the differences in engagement with the social media platform between bots and humans, we explored 4 questions with the data we have.

- Is there a difference in the amount of tweeting between bots and humans?

- Are humans good at noticing if an account is a bot?

- Do the tweets of bots receive lots of engagement from Twitter users?

- Are there noticeable differences in the twitter profile between a bot and a human?

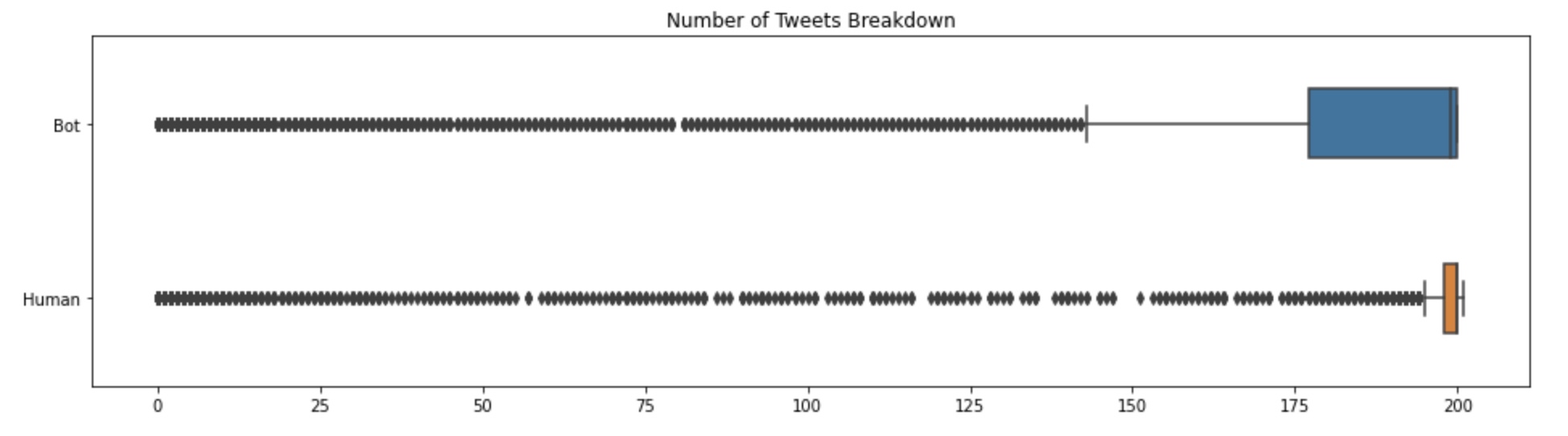

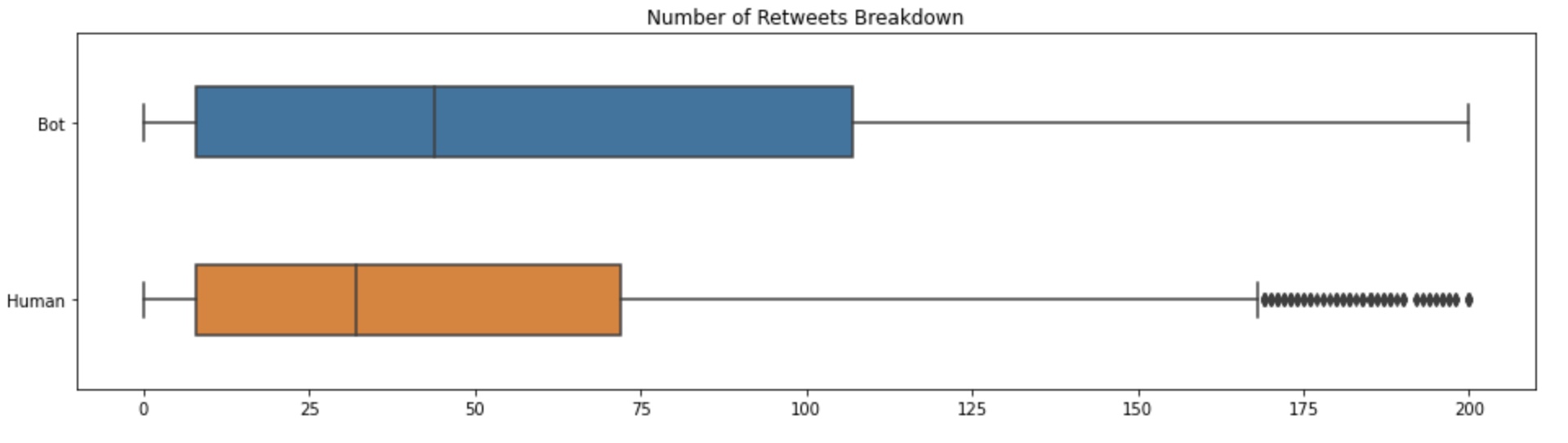

Containing over 11.8K samples in our data set, about 56% of the samples are bots and 44% are humans. Below are box plots summarizing the number of tweets and retweets across our dataset between bots and humans.

There is a noticeable difference in the spread of the number of tweets and retweets between bots and users. We notice that most humans tend to have between 185-205 tweets, with outliers spanning all the way down to 0 tweets. Bots on the other hand have a wider range between 143-200 tweets. Hence, to answer question 1: although the spread of tweets and retweets is larger for bots than humans, there is not a noticeable difference in the amount of tweeting between the two.

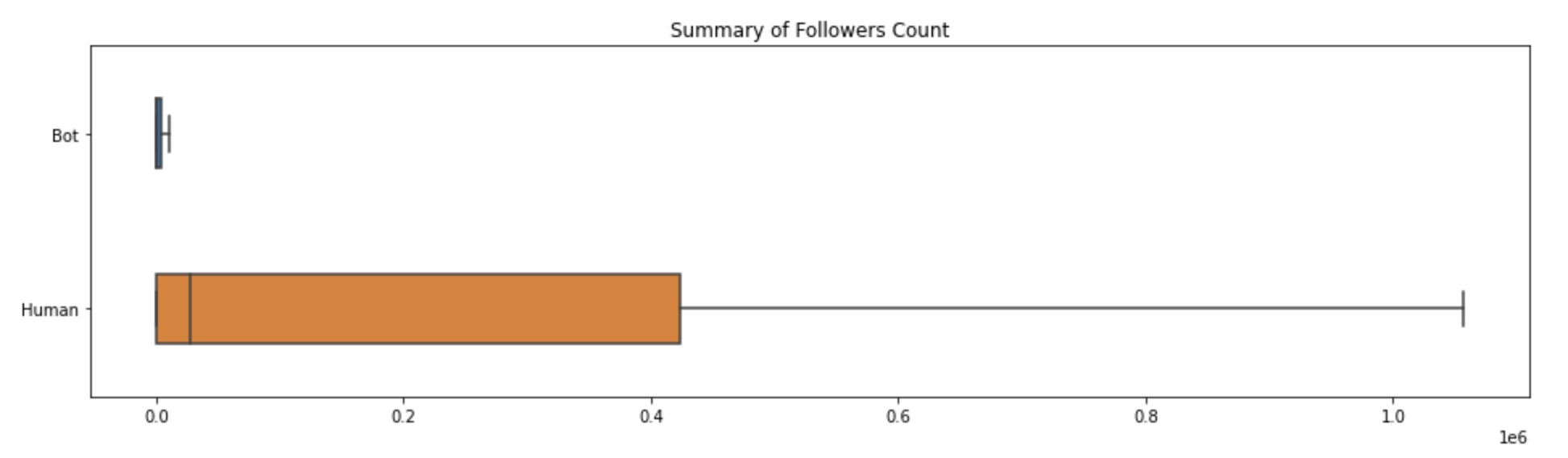

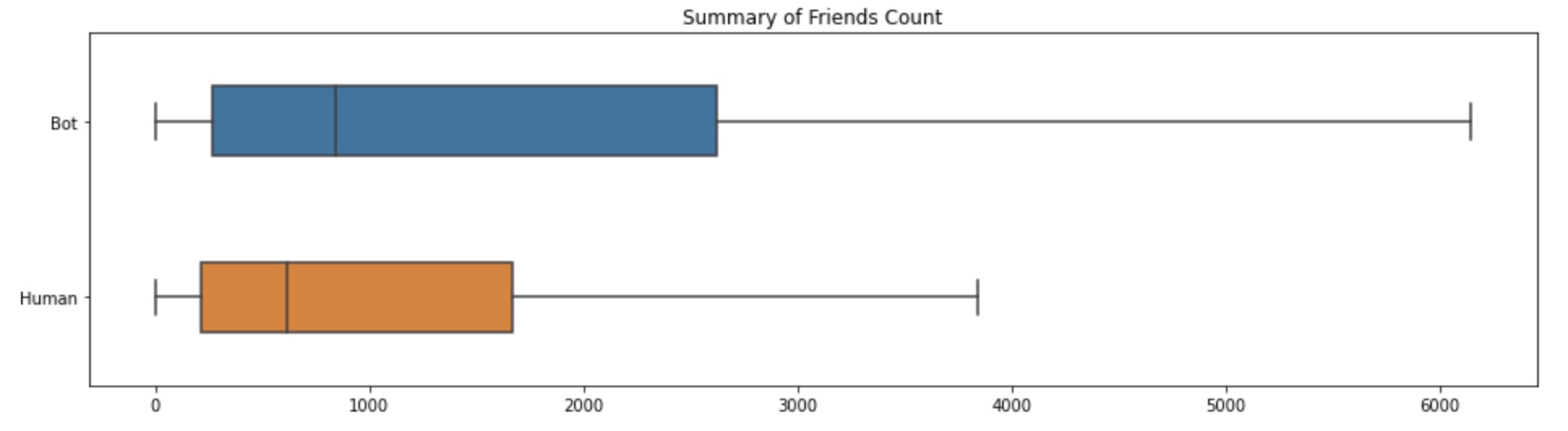

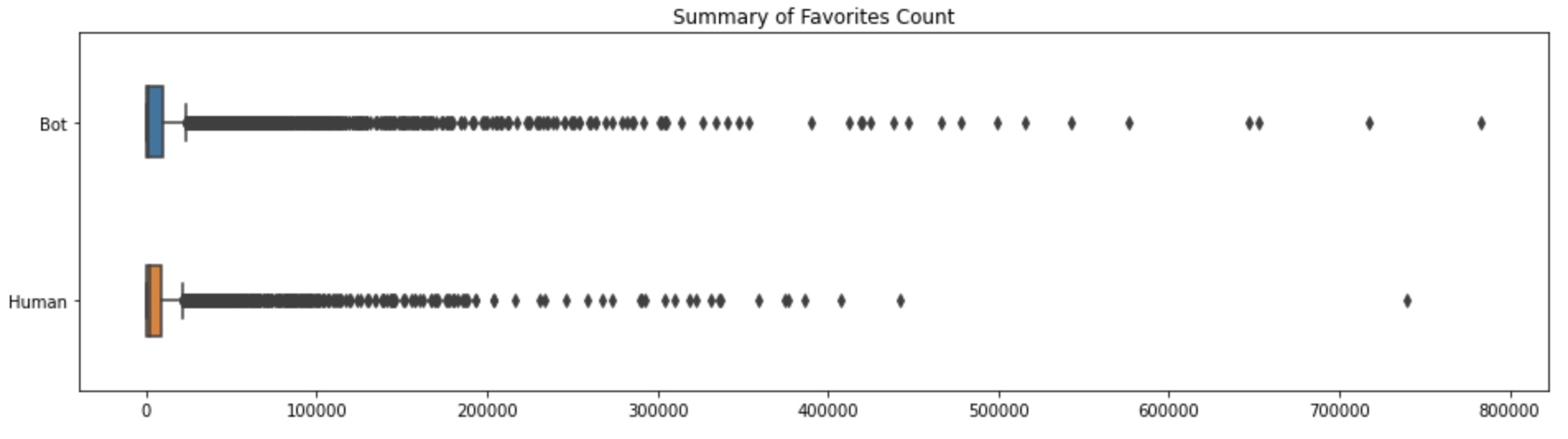

Below are box plots summarizing the spread in followers, friends (following), and favorites (total number of likes the user’s tweets/retweets have received).

It is evident that the number of followers a bot has tends to be drastically lower than the number of followers of a human. Meanwhile, bots have a much wider spread in the number of people they follow compared to humans. Hence, this suggests that humans are capable of detecting whether accounts are bots and do not follow these accounts. However, noticeably the spread in favorites count between humans and bots is shockingly similar, and the sample point with the highest number of favorites in this dataset is a bot. Thus, although humans might be able to tell that an account is a bot (maybe because the account has several of the same tweets), it is more difficult to tell if a tweet is from a bot account.

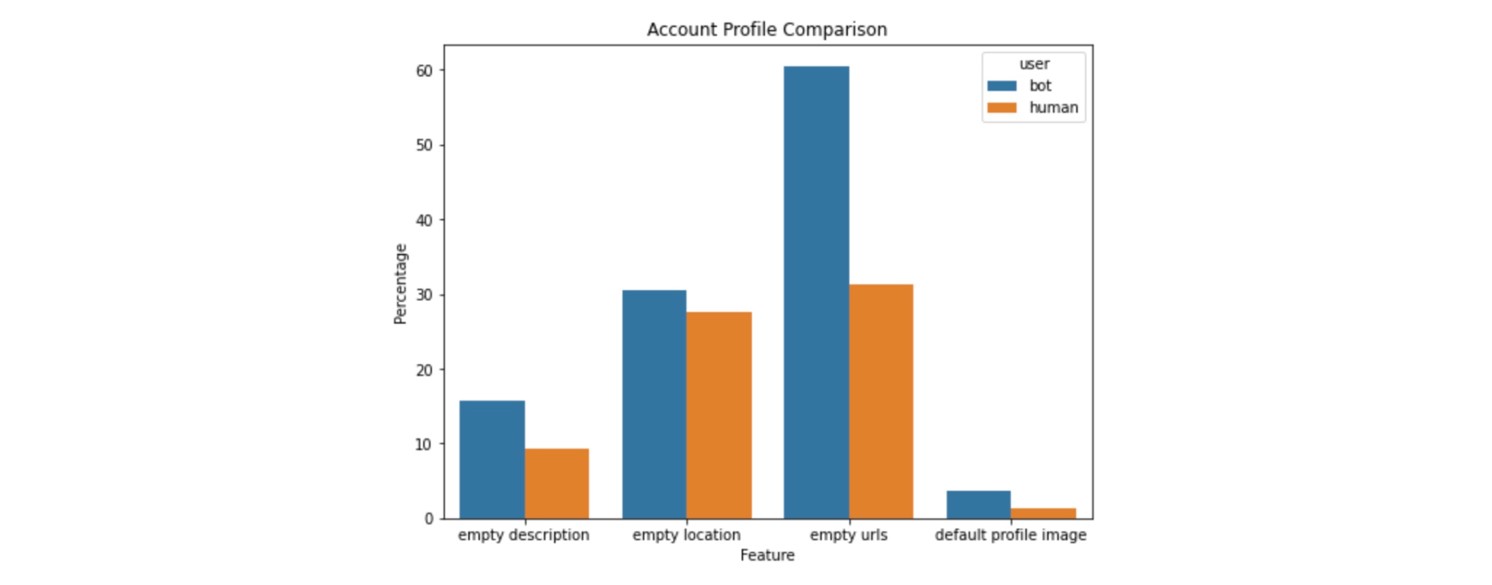

Finally, we examine whether there are differences in the profile makeup between bot and human accounts. In particular, we look at whether bots tend to have empty descriptions, locations, and/or urls compared to humans. We also compare if either group clearly uses the default profile image more than others. Below are our findings:

As expected, more bot profiles than human profiles are incomplete (i.e., have empty descriptions, locations, urls, or use the default profile image). However, the differences between the two types of Twitter users is minimal across all the categories. This suggests that bot algorithms are quite sophisticated today and motivates the need for more advanced techniques than simple heuristics to detect whether an account is a Twitter Bot or not. Thus, we present three different methods with insights in the rest of this blog for bot detection: feature-based, text-based, and graph-based methods.

Feature-Based Method

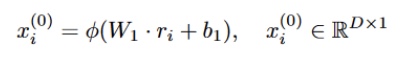

Feature-based methods mainly focus on feature engineering with profile information and employing conventional classification algorithms for bot detection. To train the models, we use few features directly from the user profile information. The remaining features are derived from other features in the dataset. The following features are used directly from the dataset:

listed_count: The number of public lists that the user is a member offollowers_count: The number of followers the account currently hasstatuses_count: The number of tweets (including retweets) issued by the userfriends_count: The number of users the account is following (i.e., their “followings”)favorites_count: The number of tweets the user has liked in the account’s lifetimeverified: Indicates whether the user has a verified account or notdefault_profile: Indicates whether the user has retained the them or background of their user profile or not

The following features are derived from other features in the dataset:

profile_image_present: Derived from theprofile_image_urlfeature which is a HTTPS-based URL pointing to the user’s profile imagescreen_name_length: Length of the screen name feature which is a handle, or alias that this user identifies themselves with.screen_name_digits: Number of digits in the screen namescreen_name_entropy: Entropy of the screen name feature (entropy is a measure of the randomness of the data, which is particularly useful for detecting bots)name_length: Length of the name feature, which is the name of the user, as they’ve defined itname_digit: Number of digits in the namename_entropy: Entropy of the namedescription_length: Length of the description feature, which is the description of the profile as provided by the userdescription_digit: Number of digits in the namedescription_entropy: Entropy of the namelocation_present: If there is a user-defined location for this account’s profile

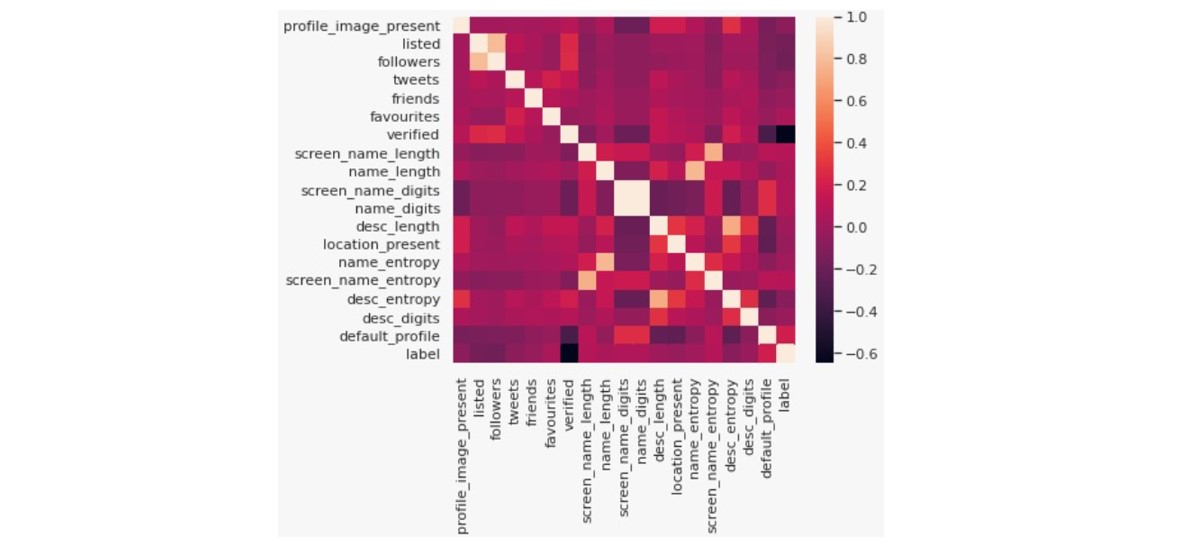

The below heatmap shows how the features are correlated among themselves and also with the label:

From the correlation map, we find that there is a strong negative correlation between the label and verified information. This makes sense as verified profiles are likely to be humans rather than bots. There also exists a strong positive correlation between the followers and the listed count. This suggests that an account with a high number of followers is more likely to be present in other users’ lists.

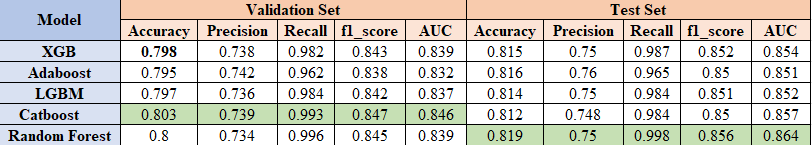

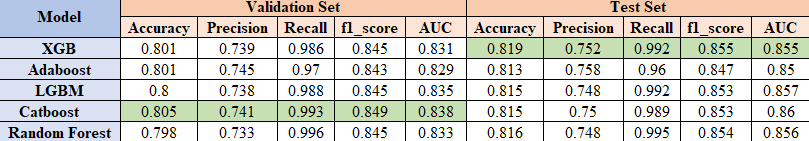

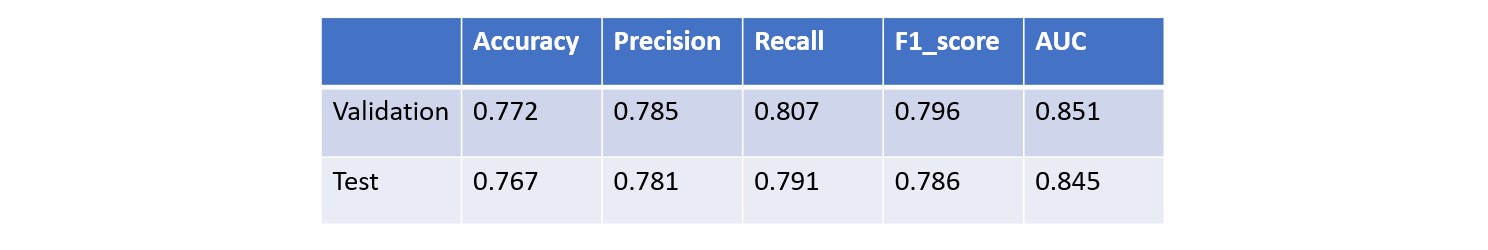

We next explore various binary classification models such as XGBoost, AdaBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, and RandomForest classifiers by performing hyperparameter tuning to improve the respective base models. The model performance (in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, f1_score, and AUC) for both the validation and test set is summarized in the table below:

We see that the Random Forest classifier performs the best in terms of test set accuracy across all the models. Meanwhile, CatBoost performs the best on the validation data set. Moreover, it was interesting to see that manually selecting and dropping certain features had a significant impact on the model performance. These decisions were influenced by the insights from the correlation table. Overall, all models achieved about 81% accuracy.

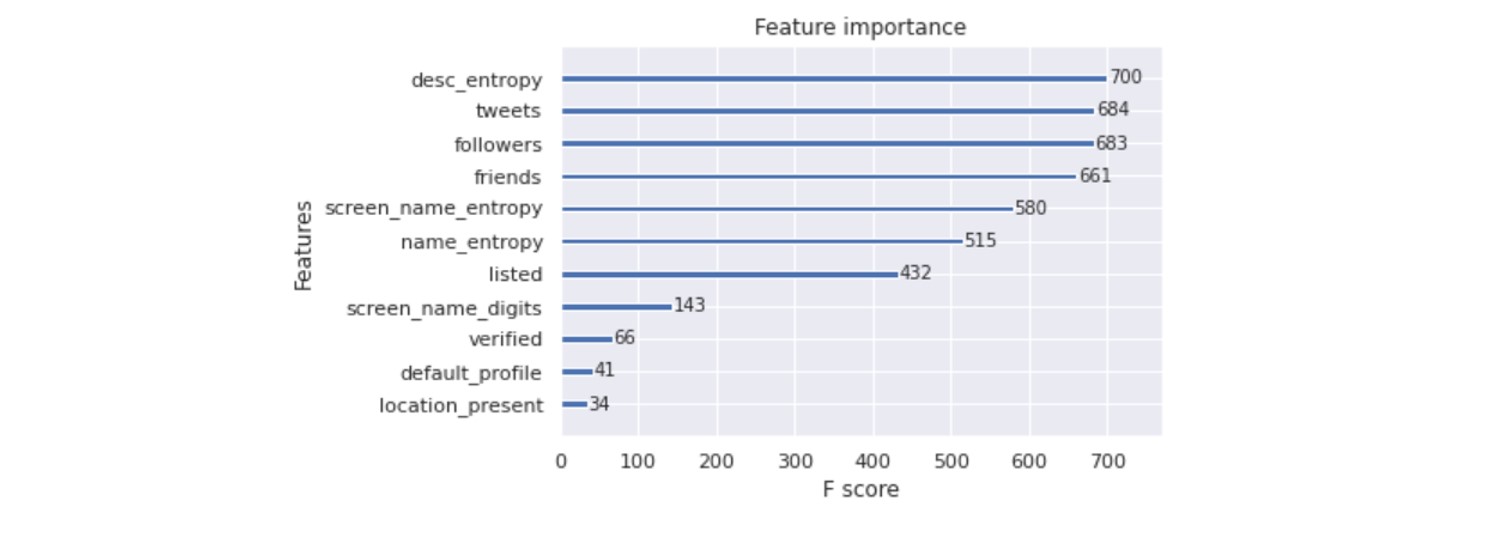

The feature importances as obtained from training the XGBoost model is as follows:

The 4 most important features that the model trains on are description_entropy, tweet count, followers, and friends.

To further explore feature engineering in feature-based methods, we use the SequentialFeatureSelector (SFS) forward selection algorithm to select features for training. This technique adds features to form a feature subset in a greedy fashion. At each stage, this estimator chooses the best feature to add based on the cross-validation score of an estimator. CatBoost is used as a base model for SFS. This run selects 11 features as the final features to be used for modeling: listed, followers, tweets, friends, verified, screen_name_digits, location_present, name_entropy, screen_name_entropy, desc_entropy, and default_profile. With these 11 features, we re-train the same classifiers that used previously. The table below shows our results.

Overall, we notice that this approach improves validation accuracy, but does not improve the test set accuracy. That is, it does not achieve an accuracy higher than 81.9%, the highest accuracy achieved in the previous experiment.

Disadvantages of feature-based method: While this method can identify the important features that can help in detecting Twitter bot accounts, the bot operators are increasingly aware of the hand-crafted features and often try to tamper with these features to elude detection. Hence, it is difficult for the feature-based methods to keep up with the competition from the evolving bots. However, this when combined with other text and graph based techniques can make the model more robust.

Text-Based Method

Text-based methods utilize natural language processing (NLP) techniques to identify bots from a user’s description and tweets. With the recent advancement in computing capability, large-scale pre-trained language models have shown excellent performance on various NLP tasks, such as language translation, sentiment analysis, summarization, and question answering. Additionally, one can fine-tune the language models on specific problems using limited amounts of training data and still obtain surprisingly good results. In particular, we use RoBERTa-large as our language model from Hugging Face and finetune it on the TwiBot-20 dataset. Our implementation is based off of the TwiBot-20 paper [4] with minor modifications.

RoBERTa [5] (Robustly Optimized BERT Pre-Training Approach) is a variant of BERT [6] (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), a popular language processing model developed by researchers at Google. RoBERTa was introduced in 2019 by researchers at Meta AI and implemented several design improvements based on BERT [6] to make it even more effective at NLP tasks. The model was pretrained with the Masked language modeling (MLM) objective, which allows it to learn an inner representation of the English language that can then be used to extract features useful for downstream tasks.

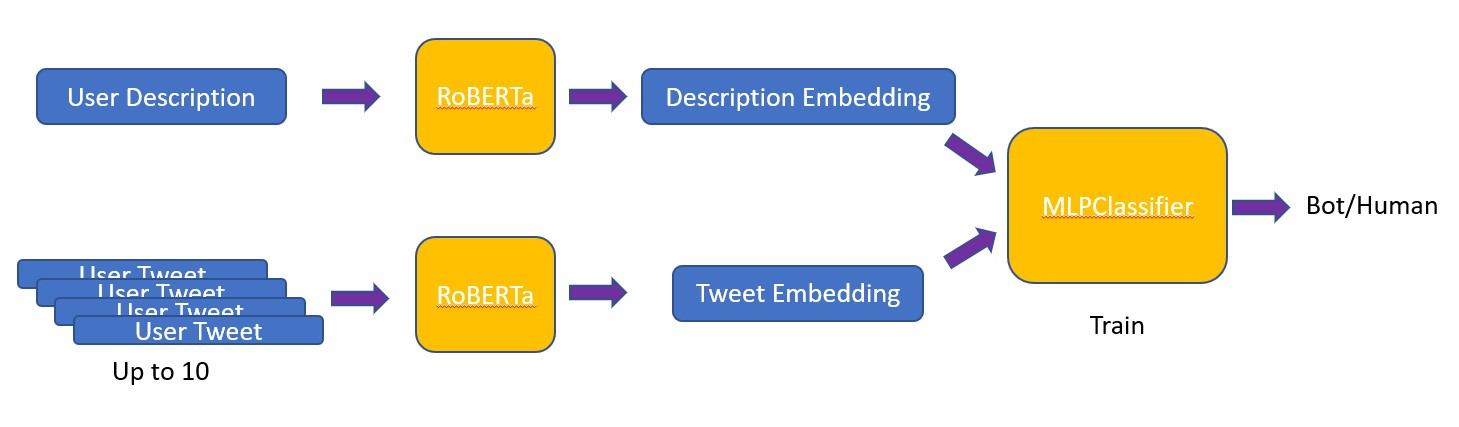

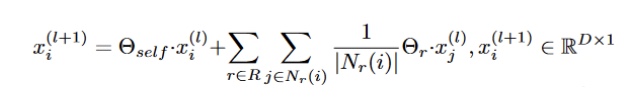

From the user description and tweets, we generate a description and tweet embedding for each user, respectively. Since a user can have up to 200 tweets in the dataset, we average up to 10 tweet embeddings to obtain a single tweet embedding for each user to save preprocessing time. We then use the description embedding, tweets embedding, and labels to train a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) head for fine-tuning. The figure below shows the architecture of our model.

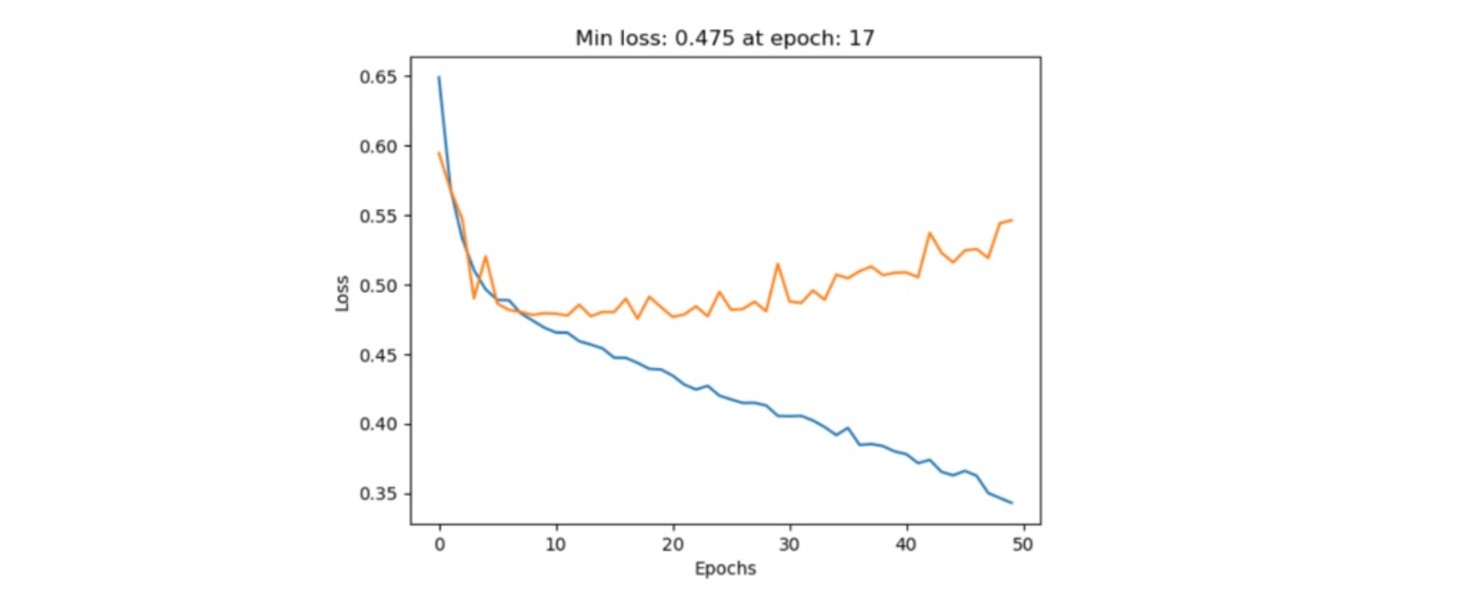

We implement our model using PyTroch and Ray Tune for hyper-parameters tuning. The parameters we search for include the hidden dimension and dropout rate of the MLP, learning rate, and weight decay value of the Adam optimizer. After obtaining the optimal parameters according to the search, we train the model on the training set and track the validation loss for early stopping. The figure below shows the training and validation loss during each training epoch. We took epoch = 17 as our final model.

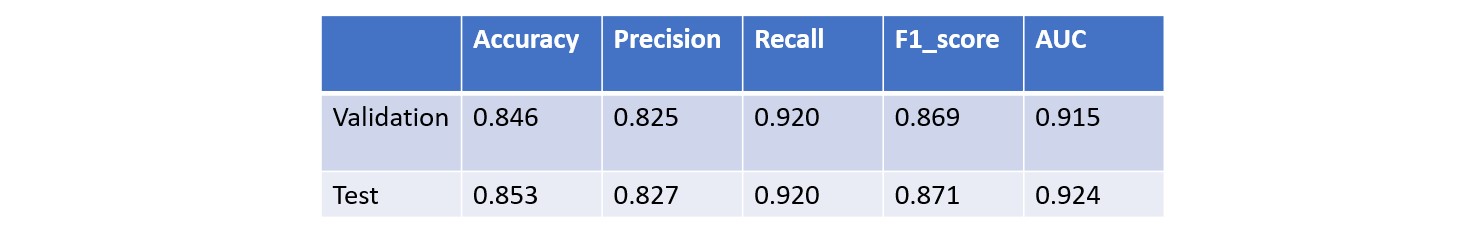

We again evaluate the performance of our model based on accuracy, precision, recall, f1_score and AUC. The result is shown in the table below.

We can see that the performance of our text-based method (test accuracy: 0.767) is not as good as the feature-based method (test accuracy: 0.819). This is reasonable as text alone may contain less information compared to the rich engineered features we use in the feature-based methods. Although these two methods utilize distinct information sources, we suspected combining the two methods would boost the overall performance. Therefore, we next integrate both methods by stacking.

Stack Feature-Based and Text-Based Method

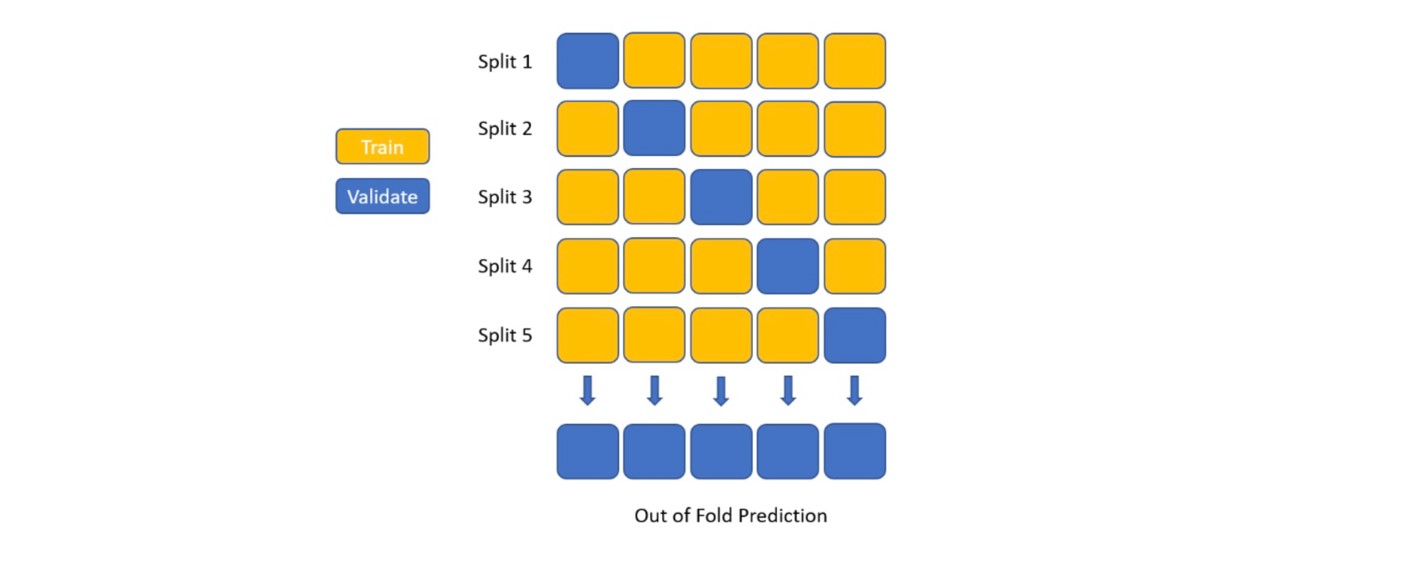

In this section, we explore stacking our feature-based and text-based methods. As shown in the figure below, we first generate out-of-fold predictions on the training set using our text-based model.

Next, we add the out-of-fold predictions from our text-based method as a new feature to our feature-based method and train a CatBoost classifier on the new set of features. The result of this model is shown in the table below.

We can see our stack model significantly outperforms both the feature-based and text-based models in all evaluation metrics. In particular, it obtains a test accuracy of 85.3% which is a 4% gain over the best feature-based method! This is the highest accuracy reported so far for TwiBot20 using both feature and text input [8]. Our experiment results support the common wisdom that stacking two independent learners (both in terms of models and features) can yield much better performance!

After exploring the property and semantic features of the TwiBot-20 dataset by feature-based and text-based models, there is one last feature left unexplored – the neighborhood feature! In the next section, we will see how the following/follower relationship between users can help us better identify Twitter Bots!

Graph-Based Method

While text and feature-based bot detection models have progressively shown good results in identifying Twitter Bots, they suffer from certain drawbacks. Bot detection techniques that rely on feature-based approaches are prone to adversarial attacks when bot developers try to temper with engineered features to avoid detection. While text-based methods are more robust to adversarial attacks, they fail when bot designers infuse malign content between genuine posts from genuine users. This makes them immune to detection using text-based approaches, which essentially try to capture the malicious nature of tweet content. Moreover, while text-based and feature-based methods capture the account behavior based on singular account details and attributes, they do not consider details on how users interact with each other. The user interaction or the social network encodes valuable information and can be leveraged to classify genuine human interaction vs. artificial bot interaction in the network. However, the major difficulty in using classical machine learning methods is that they work with Euclidean data, whereas graphical data is essentially non-Euclidean.

This is where Geometric Deep Learning models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) come into play. They accurately model data which lie in non-Euclidean manifolds. Therefore, recent studies have been focusing on developing graph-based Twitter Bot detection methods. They have proved to be very promising at addressing the challenges facing Twitter Bot detection and are exhibiting state-of-the-art performance. These methods interpret users as nodes and follow relationships as edges to leverage graph mining techniques such as relational graph convolutional networks (RGCN) for graph-based bot detection.

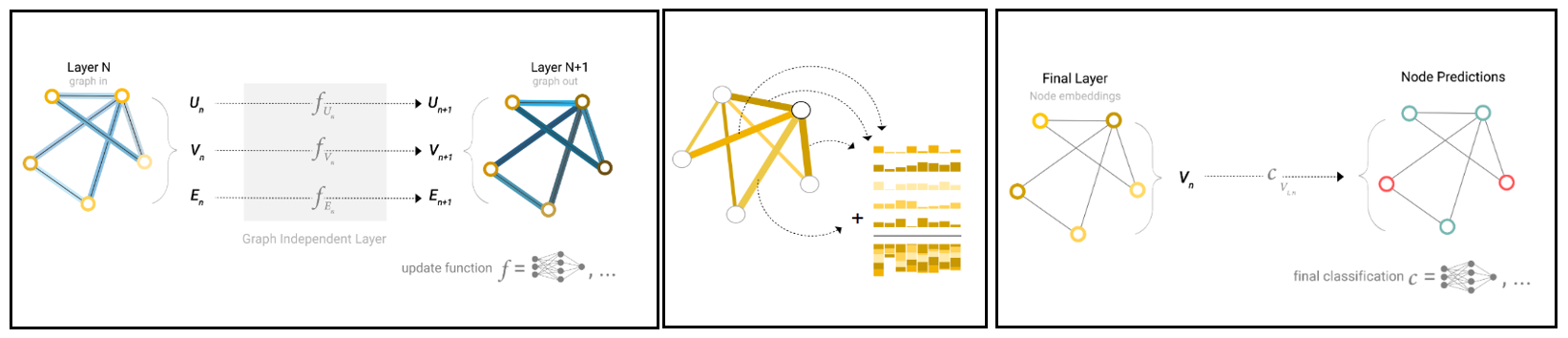

GNNs are neural network architectures that directly operate on graph structures and therefore allow node, edge, and graph level prediction tasks. While many different GNN architectures exist, the simplest GNNs use the “message passing neural network” framework. In a simple sense, a geometric graph consists of nodes, edges, and some connectivity information, which can be cast as a GNN with the corresponding node features, edge features, and connectivity information in the form of adjacency matrix. This blog post’s illustration shows how GNNs work:

- A simple GNN uses a separate neural network to operate on each of the embeddings on each component (node, edge) of the graph to get back a learned embedding in the next GNN layer.

- In the next step, all the information is pooled using an aggregation function which aggregates node and edge information connected to a particular node.

- This aggregated information is passed on to the forward layer via an activation function.

The development and evaluation of graph-based Twitter Bot detection models is hindered by existing datasets. The Bot Repository3 provides a comprehensive collection of existing datasets. Of the listed datasets, only three provide the graph structure among Twitter users: Cresci-2015 [Cresci et al., 2015], TwiBot-20 [Feng et al., 2021c], and TwiBot-22 [Feng et al., 2022].

We replicate [8] the recent FTG method - BotRGCN [Feng et al., 2021b] - on the TwiBot-20 dataset where F, T, G denote Feature, Text, and Graph-based, respectively. We selected the BotRGCN model as it gives the highest accuracy among all feature, text, and graph-based methods on the TwiBot-20 dataset. Next, we explore different variants of the BotRGCN method. Finally, we also look into generating embeddings using other pre-trained NLP models like RoBERTa and BERT. The remaining paragraphs explain the BotRGCN method followed by the experimental results.

Bot detection with Relational Graph Convolutional Networks (BotRGCN) [7] uses the power of GNNs to capture network interactions to address detection issues that cannot be dealt with text and feature-based models, as explained above. BotRGCN uses necessary numerical and categorical user information along with pre-trained language models.

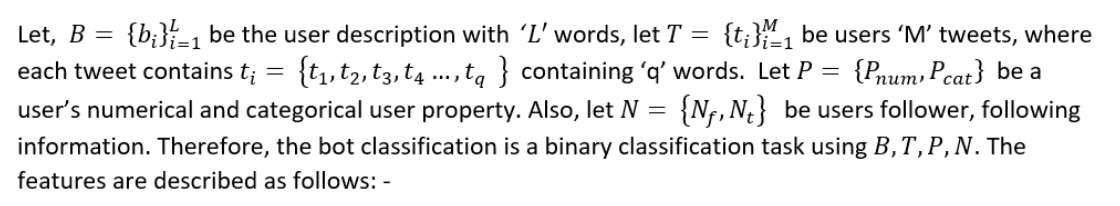

Below is the problem description for our BotRGCN model:

Feature Embeddings: The original user features - description, tweet, numerical and categorical features - are encoded and concatenated before they are fed to GNN. The embeddings are generated using two methods: pretrained (i) RoBERTa and (ii) BERT transformer language models, whereas rnum and rcat are derived using one-hot encoded features fed into a fully connected autoencoder with leaky-relu activations.

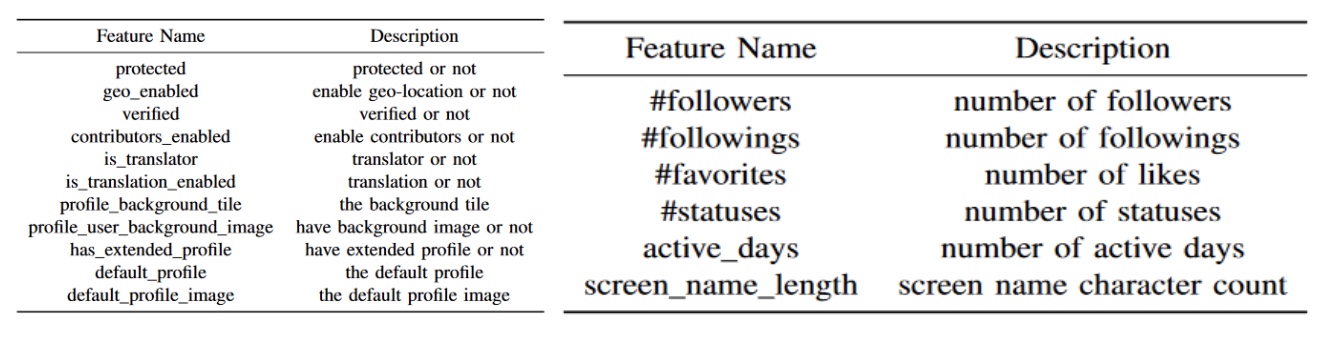

Architecture: BotRGCN incorporates the twitter network using relational graph convolutional networks to learn user representations and network relations. The RGCN derives the hidden representation by passing the input through the first layer and then applying the activation function. $W_1$ and $b_1$ are learnt here.

The following aggregation operation combines information from the neighbors. Here, $N_r$ is the neighbor node.

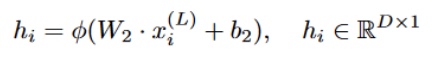

In the final layer, the output of the MLP is:

where $W_2$ and $b_2$ are learnt. Finally, BotRGCN uses the cross-entropy loss with L2 regularization:

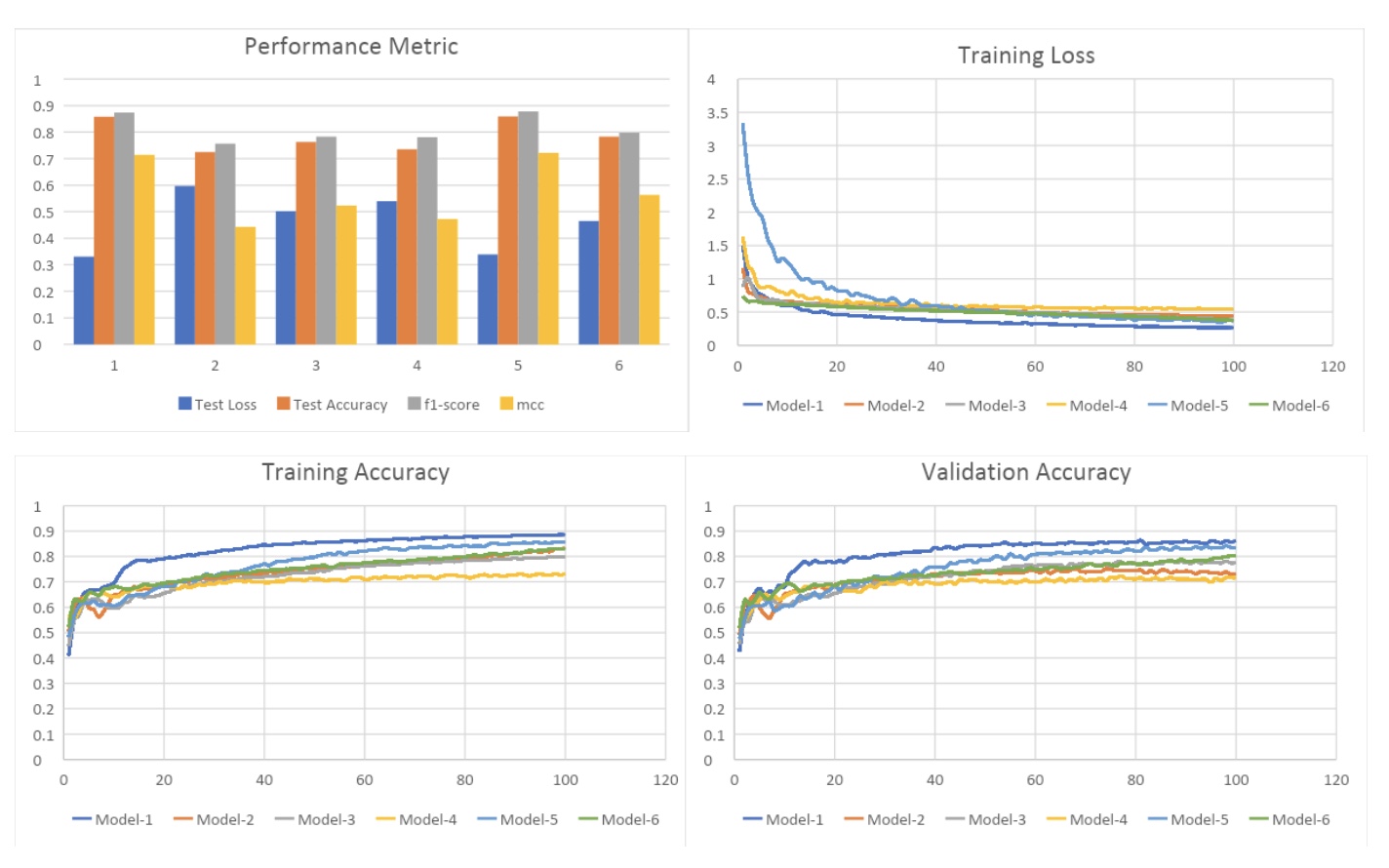

We train the the BotRGCN model as implemented in [7] as our baseline model. In addition, we train 5 other variants with different settings/architecture. Below is the summary of the 6 models and their differences:

- Model 1: Base RGCN (with RoBERTa)

- Model 2: RGCN with BERT

- Model 3: Model 3: RGCN without user description

- Model 4: RGCN without tweets

- Model 5: RGCN with GAT layer (side note: this blog post does an excellent job explaining what GAT layers are)

- Model 6: RGCN with 2 RGCN conv layers

Models 1 and 2 use different language models, namely RoBERT and BERT, to understand the influence text feature embeddings have on the network. Moreover, we train an RGCN model without user description (model 3) and one without user tweets (model 4) to evaluate how important these features are in prediction accuracy. Finally, our last two models each use a different architecture. Model 5 uses a Graph Attention Network (GAT) layer, which differs from GCN’s in the way neighborhood information is aggregated. GAT introduces an attention mechanism in contrast to the normalized convolution operation that is used by GCNs. This is known to improve generalizability since the aggregation operation becomes less structure dependent. Model 6 uses the base RGCN model with two RGCN convolution layers.

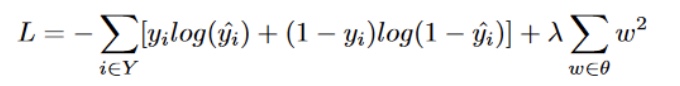

Below we present a side-by-side comparison of our 6 models with the various performance metrics we obtained. We also include the change in training loss, training accuracy, and validation accuracy over epochs. Finally, we present the raw performance scores for our 6 models.

We see that BotRGCN Model 1 achieves accuracy, f1 score, and MCC of 85.8%, 0.8735, and 0.7145, respectively. Model 2 shows a drop in accuracy which is expected since RoBERT is optimized (uses dynamic masking, more data points, large batch size) and hence a better variant of BERT. Model 3 and 4 justify the importance of multi-modal user information which is evident by the fact that the accuracy drops when either the tweet or user description features are not included while training. The use of a GAT layer in model 5 shows similar results to the baseline BotRGCN, suggesting that the extra complexity of using a GAT layer is unnecessary. Finally, the use of two RGCN layers in model 6 is not any better.

Overall, we see that BotRGCN outperforms the text-based and feature-based models. This shows the significance of inculcating neighborhood connectivity information for Twitter Bot detection and exploring graph-based methods and datasets in the future.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we explore multiple approaches for Twitter Bot detection - feature-based, text-based, stacking of feature and text-based, and graph-based methods. Overall, we obtain similar accuracies of 85.3% and 85.8% for the stacking solution and graph-based method, respectively. The reason behind similar accuracies is that the implemented graph-based model is not using our feature engineering that is used in the stacking solution to generate embeddings. The insight behind stacking solution working this well is that neural network models do not perform as well as tree-based methods on tabular data. Nonetheless, the fact that the graph-based model is still performing a little bit better than the stacking solution shows the significance of neighborhood information in Twitter Bot detection. Therefore, graph-based methods are definitely promising future direction for Twitter Bot detection!

GitHub Artifact

References

- [1] Ashok Deb, Luca Luceri, Adam Badaway, and Emilio Ferrara. 2019. Perils and Challenges of Social Media and Election Manipulation Analysis: The 2018 US Midterms. In Companion Proceedings of The 2019 World Wide Web Conference (San Francisco, USA) (WWW ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1145/3308560.3316486

- [2] Emilio Ferrara. 2017. Disinformation and Social Bot Operations in the Run Up to the 2017 French Presidential Election. CoRR abs/1707.00086 (2017). arXiv:1707.00086 http://arxiv.org/abs/1707.00086

- [3] Jonathon M Berger and Jonathon Morgan. 2015. The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter. The Brookings project on US relations with the Islamic world 3, 20 (2015), 4–1.

- [4] Shangbin Feng, Herun Wan, Ningnan Wang, Jundong Li, and Minnan Luo. 2021. TwiBot-20: A Comprehensive Twitter Bot Detection Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (CIKM ‘21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 4485–4494. https://doi.org/10.1145/3459637.3482019

- [5] Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692, 2019. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11692

- [6] .Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In North American Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL). https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

- [7] Feng, Shangbin, et al. “BotRGCN: Twitter bot detection with relational graph convolutional networks.” Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.13092

- [8] Feng, Shangbin and Tan, Zhaoxuan and Wan, Herun and Wang, Ningnan and Chen, Zilong and Zhang, Binchi and Zheng, Qinghua and Zhang, Wenqian and Lei, Zhenyu and Yang, Shujie and Feng, Xinshun and Zhang, Qingyue and Wang, Hongrui and Liu, Yuhan and Bai, Yuyang and Wang, Heng and Cai, Zijian and Wang, Yanbo and Zheng, Lijing and Ma, Zihan and Li, Jundong and Luo, Minnan. 2022. TwiBot-22: Towards Graph-Based Twitter Bot Detection.In Proceedings of the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04564